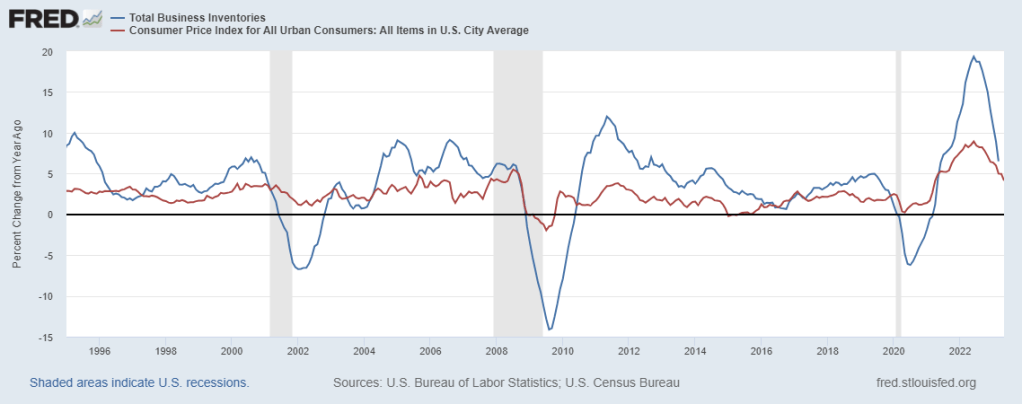

Or, do sharp inventory drops predict recessions?

The Phillips Curve hypothesis holds that inflation and unemployment have a stable, inverse relationship.

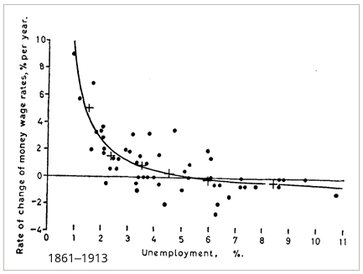

In 1958, William Phillips wrote “The Relation between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861-1957”, which was published in the quarterly journal Economica. Phillips claimed an inverse relationship between money wage changes and unemployment in the British economy over the period examined.

In 1960 Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow took Phillips’ work and made explicit the link between inflation and unemployment: when inflation was high, unemployment was low, and vice versa.

Here’s the data he used.

Rate of Change of Wages against Unemployment, United Kingdom 1913–1948, Phillips (1958)

For those with stats background, please don’t laugh at this point. Actually, please do – I lost it when I first read this paper.

Of course, all that evaporated (or should have) with the 1970s stagflation — high levels of both inflation and unemployment.

Still, true believers don’t slip away and the debate continues.

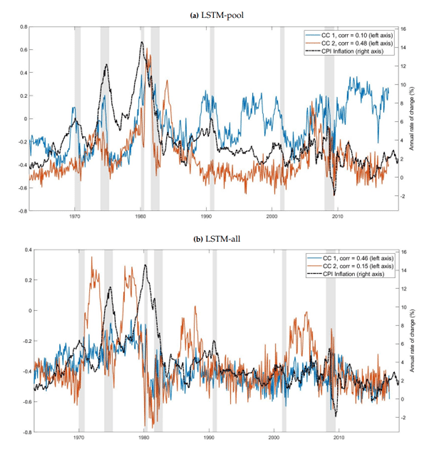

Does inflation behave nonlinearly with respect to other macroeconomic variables? If so, which variables and what are the eigenvalues?

As reported by Paranhos, 2021, neural networks beat common benchmarks mainly at medium-long horizons (most of the models are significantly superior to benchmarks at the two-year forecast horizon).

The long-short term model (LSTM) better forecasts performance than the feed-forward neural network, controlling for the same information set.

Paranhos further holds macroeconomic information, as opposed to CPI data only, is important to forecast inflation during the Great Recession and in its aftermath, a result that is in line with other works in the literature suggesting that economic information plays a substantial role in the prediction during episodes of high uncertainty (Chakraborty and Joseph, 2017, Medeiros et al., 2019).

Last, the output of the LSTM model provides interesting insights on the signals of the economy that are particularly important to predict inflation.

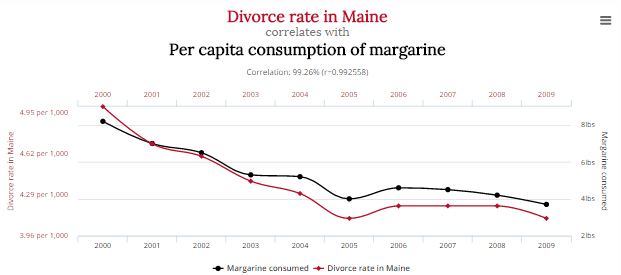

Of course, always be careful of correlations.

Correlation does not imply causality.

Buy the dip?

References:

Chakraborty, C., and A. Joseph. (2017). “Machine learning at central banks.” Bank of England

Working Papers 674.

Medeiros, M. C., G. Vasconcelos, A. Veiga, and E. Zilberman. (2019). “Forecasting Inflation in a

Data-Rich Environment: The Benefits of Machine Learning Methods.” Journal of Business &

Economic Statistics 1–45.

Paranhos, Livia. (2021). “Predicting Inflation with Neural Networks.” Arxiv-econ arXiv:2104.03757