On St. Patrick’s Day, Charles Hugh Smith succinctly summarized the melt-up of the US economy (https://www.oftwominds.com/blogmar21/dead-money3-21.html)

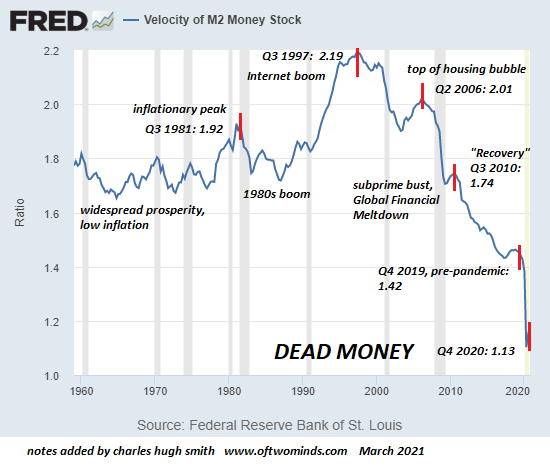

In the era of widespread prosperity in the 1960s and 1970s, the velocity of money ratio remained in a band between 1.7 and 1.8, moving up toward 2 in the inflationary late 70s as it made sense to trade cash that was losing value for goods and services before it lost even more purchasing power.

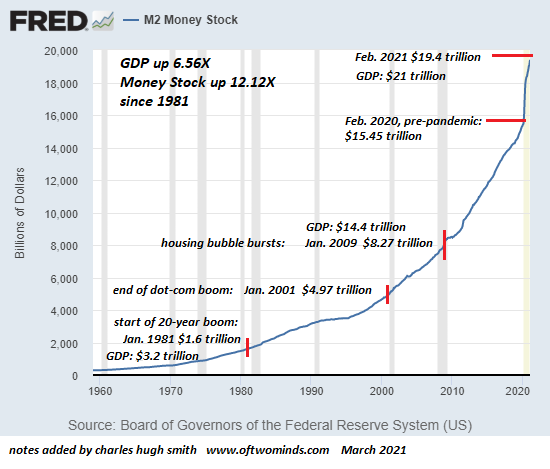

Velocity returned to this range in the 1980s boom, and then rocketed to postwar highs at 2.2 in the Internet boom of the 1990s. Since that top in 1997, money velocity has been in a secular decline. As every Fed-inflated financial bubble pops, money velocity takes another leg down. Even before the pandemic, it was in a steady free-fall even as the supply of money steadily rocketed higher.

So what do we make of this stunning expansion of money and equally stunning collapse of money velocity? Ours is a Dead Money Economy. New money is created in the trillions of dollars, but it is either shipped overseas to exporters selling goods to Americans or it’s being stashed somewhere rather than being exchanged for domestically produced goods and services.

The rest of Smith’s piece expands on this obvious dynamic. But let’s pick up with the “how” of these dynamics with Weimin Chen’s note (https://www.austriancenter.com/what-the-shipping-container-shortage-reveals-about-us-china-trade/), in which he focuses on the stunning levels of shipping container flows.

Despite the record unemployment rate, widespread hardship to businesses, strains on the healthcare system, political turmoil, and general disruption to daily life in 2020, U.S. consumers have managed to ramp up their habit of buying things. Demand for physical goods replaced some of the previous demand for in-person service-related experiences and much of that demand was met with a surge of imports from China as domestic production slowed down due to lockdown measures. Up until recently, global supply chains managed to find their footing and could meet demand, but news has emerged that reveals stresses on the world’s shipping infrastructure and uncovers clues about the economic outlook.

Container Shortage and Chinese Exports

Global logistical networks recently began to suffer from a shortage of shipping containers as demand has suddenly risen. Freight rates from China to the U.S. have jumped by 300%. The container situation has become so extreme that hundreds of thousands of containers have been sent off empty from U.S. ports, mostly to China as exporters demand empty containers with increasing urgency. An estimated 177,938 containers, were rejected from loading U.S. export items at the ports of Los Angeles and New York/New Jersey alone and then sent across the Pacific.

The recent imbalance of shipping containers illustrates the latest state of affairs surrounding the US and Chinese economies. As exports of consumer goods from Asia eclipse exports of mostly commodity and raw materials from the U.S. — in this case, even blocking US agricultural exports from having shipping containers to reach foreign markets — the trade deficit between the two countries may become more important to these highly competitive economies.

When Trade Deficits Matter

The Austrian perspective on the U.S. trade deficit has long been that given the continued relative productivity of the U.S. economy, foreign desires to invest in the U.S., and demand for the dollar abroad, the trade deficit is a ‘pseudo-problem.’ The US competitive advantage vis-à-vis other countries in recent decades has made running a trade deficit highly probable and even favorable for Americans as they enjoy the consumption of cheaper imports.

Thus far, the parties involved have been satisfied with this arrangement as U.S. consumers bring in goods at favorable prices and producers receive a reliably stable world reserve currency; the U.S. dollar. However, the underlying conditions particular to the U.S. economy in relation to China may be changing. There are two aspects of the U.S.-China trade deficit that merit attention. The first is the effect of net consumption by the U.S. coupled with dovish monetary and fiscal policies whereas the second is what China plans to do with U.S. dollar accumulated through exports.

On the U.S. side of the equation, easy money from the central bank coupled with fiscal stimulus extended to consumers has juiced buying activity as the lockdowns have forced people to stay home and spend. It’s no wonder that shipping containers are rushing to get back to China. With the U.S. taking big hits to production and foreign investment in 2020, along with explosive increases in the money supply, critical questions arise regarding the nature of this trade deficit and how long the status quo can continue as the country pushes the boundaries of its exorbitant privilege. Indeed, the health of the dollar itself as it relates to trade deficits would be an indicator to watch in coming years.

In running a trade surplus with the U.S., China has traditionally exchanged its U.S. dollars for U.S. Treasuries to add to its balance sheet and to maintain its export advantage. In recent years, however, China has reduced its holdings in Treasuries. This trend has also coincided with massive spending on the part of China in the last decade on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) infrastructure and trade corridor project which involves 71 countries across Eurasia and Africa that encompass two-thirds of the global population and one-third of world GDP.

Given the continued global dollar demand, it would be shrewd for China to use accumulated dollars to acquire foreign assets and invest in projects that have the potential to generate future income. The trade war with the US in recent years has driven China to deepen its flow of trade toward surpluses with other emerging markets and forge strategic global relations.

As containers carry goods from China to the U.S. and rush to return empty to bring more, the moment provides a glimpse into a potentially precarious arrangement between the two countries. While the U.S. presently consumes itself into debt and liabilities, China has leveraged its productive surpluses from this relationship into increasingly influential assets that may strengthen its position and further challenge the U.S., and perhaps even the dollar itself.

Peter Schiff this tale a punchline (https://schiffgold.com/guest-commentaries/what-is-the-shipping-container-shortage-telling-us-about-the-economy/).

The annual trade deficit for goods came in at an all-time high in January, increasing $3.4 billion to a record $221.1 billion. In another sign of the massive trade imbalance, there is a shortage of shipping containers to bring things into the US.

In a nutshell, the Federal Reserve is printing money and the US government is giving it to unemployed people who aren’t producing anything. As Peter pointed out, “They’re buying the stuff that people in other countries are employed making.”

“So, it’s the productivity of the rest of the world that Americans are living off of, and the trade deficit evidences that and shows you that our whole economy, our whole recovery, is a fraud.”